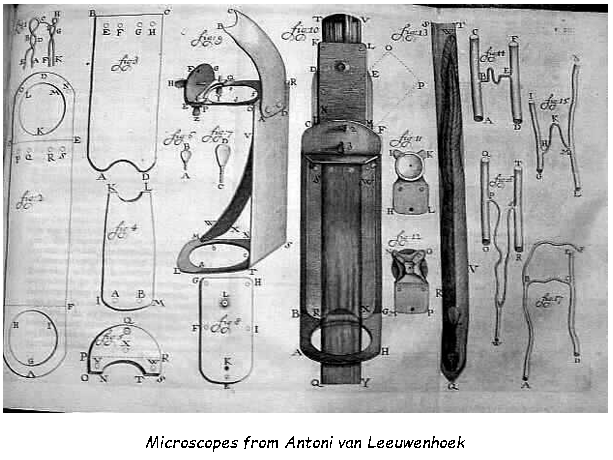

On the other hand, there was also the technology here to enlarge the very small things. Antoni Leeuwenhoek built on this and built a microscope with which he could magnify hundreds of times. The cloth trader by profession, who studied hobby microscopy as a hobby, was able to see and describe things that had never been observed before because of his strong microscopes. The description that sperm consisted of living sperm cells is perhaps most appealing to the imagination.

We can hardly imagine it, but many scientists in the seventeenth century qualified in the craft of lens grinding. And not just for the purpose of building a microscope or telescope. René Descartes, for example, the French philosopher, spent twenty years in the Netherlands and at that time qualified in grinding lenses. Baruch Spinoza was a famous lens sharpener. It was a fascinating technique that tilted the world view because of the new insights it yielded. In addition, lenses were used so much that it was also possible to earn a living.

In his time, the second half of the seventeenth century, Christiaan Huygens improved the Dutch viewer enormously and designed meters-long telescopes. From his hand come the first detailed descriptions of the moons and rings around the planet Saturn.

In the Boerhave Museum in Leiden, one can admire many instruments and one can get to know them better.

Changing Worldview

Dr. Robert Gorter: “During the fifteenth century, there was a breakthrough in how people experienced themselves and the world around them, which led to the beginning of the current fifth post-Atlantic culture period. Today, the world is being studied and analyzed through the senses. A microscope or telescope can be seen as an “extension of seeing”. Experiencing and thinking strongly religious and mystical until then makes way for a science based on the reproduction of observed phenomena and empiric and logical thinking. Aristotle had already laid the foundation for logical thinking in his “Ten Catagories.”

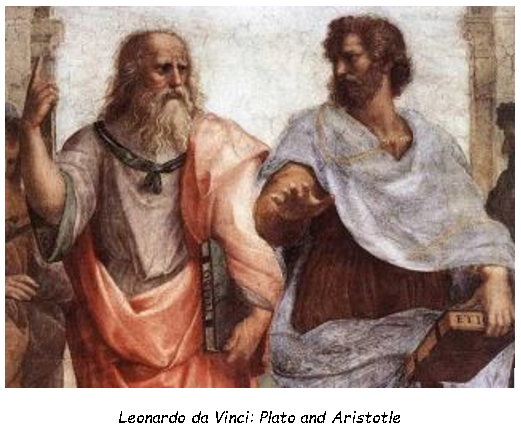

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher who is also called the most universal philosopher of antiquity. He wrote on countless topics ranging from the basics of physics to ethics and politics. He was the student of Plato and the teacher of Alexander the Great. He also founded his own school in Athens, the Lyceum.

A category or predicate type is a concept in philosophy and logic that refers to the most general characteristics of the predicate, the property of something. The word “category” comes from the Greek and initially meant “accusation”; they meant what can be said about something or someone.

Categories are always classifications according to the most general characteristics of predicates, but one can look at predicates in several ways. If one regards predicates as things that refer to reality (as in Aristotle’s metaphysics or ontology), then these categories are called metaphysical categories or predicaments (in English: categories of being); on the other hand, if one is interested in the logic or content of the conceptual framework (or in epistemology or in its study as in Kant), then one is talking about logical categories.

Category in Greek philosophy

In his Sofistes dialogue, Plato addresses, among other things, the problem brought to the attention of the Sophists, how we can say of something that it is (something) and is not (something else), that is to say that something is and at the same time is not. The ‘Megarian’ problem also plays a role: can we even say that a horse is big, what gives us the right to pronounce something other than: horse is horse?

From our perspective, only different meanings of the Greek verb are confused here (such as: being the case, existence, being equal to), and it is difficult for us to imagine how problematic it was to refute this (philosophically speaking).

Plato tackled this problem without letting go of his theory of ideas, so without making it a formal, logical or linguistic problem. In earlier dialogues, these ideas have always been discussed in terms of eternal, stand-alone transcendent entities. In the Sofistes dialogue (p. 254-259), however, he comes to the conclusion that there are Ideas that can combine with each other. Looking at the three Ideas Movement, Rest and Being, one has to conclude that the Idea enters into combinations with Movement and Rest, both are after all. Furthermore, all three are the same as themselves, and different from the others, so they all combine with the Ideas Identity and Difference. These five Ideas are sometimes called Plato’s five highest genera, but it is relevant here that it is very difficult to disentangle how something can be (exist) and not be (that is, be different from something else).

Plato had previously explained the “problem” that one individual can be both beautiful (compared to someone) and ugly (compared to someone else) by saying that this individual participates in both the Beauty Idea and the Ugly Idea.

Aristotle now could continue from here, and say (Metaphysics Z) that being is used in multiple ways, and hence coming to its categories, the unraveling of the verb are:

Socrates is a man (substance, so in the sense of existence as a man; cf. the Dutch, in essence, he is a man.)

Socrates is intelligent (quality)

Socrates is small in relation to Alcibiades / large in relation to Xantippe (relationship)

Socrates is in Athens (located), etc.

For this he used the word katègoria (that which we can say about something). In his writing De Categories, Aristotle recognizes 10, elsewhere he mentions fewer. The only constant factor is that the substance category always occupies a separate place compared to the others.

It must be added that elsewhere in his work these categories function more as a classification of all that is, so that category becomes more an ontological than a logical term. The following can be explained as an explanation: Aristotle says that being verb is used in several ways, but not that “the” language Aristotle knew.

It must be added that elsewhere in his work these categories function more as a classification of all that is, so that category becomes more an ontological than a logical term. The following can be explained as an explanation: Aristotle says that the verb being is used in several ways, but not that ‘the’ language (Aristotle only knew Greek) is defective, or is unable to adequately represent reality. He does not take that distance. But because, according to him, man can know the reality that surrounds him, and because he is attached to the language with which it is described, there is a mixture between the ontological and logical domain. Hence this lack of clarity as to whether the categories are intended as an unraveling of the meanings of the verb, or as a classification of all that is.

The Stoics recognized four categories: Substance, Property, Being in a certain state, Relating to something else. For them this was a classification of all that is, and not a reflection on what can be said.

Aristotle was born in 384 BC. in Stagira, a city in the north of Greece. He grew up in a family of doctors and soon became interested in biology and anatomy. His father was a doctor at the Macedonian court, which would play an important role later in Aristotle’s life. Aristotle was married to the adoptive daughter of a politician friend and at least had one son, Nicomachus.

Athens

When Aristotle was a teenager, he left for Athens to study at the Plato Academy. He was Plato’s best student for twenty years and was influenced by his teachings. Yet he also criticized Plato’s work. For example, he rejected Plato’s famous theory of ideas, in which he stated that everything we perceive is a reflection of an eternal and perfect Form. From his interest in nature, Aristotle focused more on empirical forms of research. For example, he studied the behavior of plants and animals and stated that we categorize our observations with the mind. These perceptions form the basis of our thinking, and not so much the abstract Ideas (or Forms) of Plato.

The work of Aristotle Aristotle is considered the most universal thinker of antiquity. He wrote hundreds of works on various topics. He wrote not only about biology, but also about the basic principles of science, politics, ethics, logic, mathematics and art. He worked as a teacher and taught both small groups of advanced students and a large audience. His writings therefore consist of notes that he used for scientific purposes and also of books for a large audience. His work has for the most part been lost, but his notes still form a large oeuvre.

Ethics and politics

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle wrote a lot about ethics and politics. Both philosophers believe that the ideal state should be based on just laws and virtue. Aristotle was the first philosopher to systematically develop a complete virtue ethic. From his interest in biology, he sketched the human being as a biological being that has a certain task or function. According to the philosopher, everything in nature has its own purpose or function. For example, it is the function of an apple to grow into an apple tree. This principle of efficiency also applies to humans. Man’s goal is to grow into a mature being who strives for happiness.

Good Fortune

Aristotle was the first philosopher to systematically work out the concept of human happiness. Man does not only become a fully-fledged being in a biological sense, the pursuit of happiness is a typical human affair. The philosopher wonders why we actually perform certain actions and concludes that the ultimate goal of all action is happiness. By that he does not mean that man feels happy, but leads a good life, which means a virtuous life for Aristotle. In his famous work the Ethica Nicomachea he therefore pays a lot of attention to the question of what happiness is and how people can achieve this. For Aristotle, a virtuous person is someone who acts wisely and justly and develops certain virtues of character, such as bravery, generosity, and kindness. These virtues were useful to Athenian citizens, who became increasingly involved in the democracy that developed in Athens. In addition, Aristotle sees the development of the Greek policy as an extension of human nature. Man needs the policy to survive, and cannot live without friendships. This is how Aristotle makes his famous statement: “Man is a political animal.”

Alexander the Great

Aristotle taught the men from Athens who held positions in democracy. His most important student, however, came from Macedonia and was called Alexander III, alias Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). The father of Aristotle had been a doctor at the court of Macedonia, which at that time was governed by Alexander’s father, Philip. In 342 BC. Aristotle was asked to come to the court of Macedonia to become the teacher of Alexander there. After a few years, Alexander started to rule himself and Aristotle returned to Athens, where he founded his own school, the Lyceum.

The Lyceum

Just like his teacher Plato, Aristotle also founded his own school in Athens. In 335 BC he founded the Lyceum, which was named after the place where it was, namely on a site dedicated to Apollo Lykeios. The students of the school were known as the peripateticians, to the corridors (“peripatos”) where they would study. Aristotle worked here as a researcher and teacher and had a large library built, as well as a natural science collection of plants and animals from all over the world. It is known that Alexander the Great had instructed his staff to send all kinds of specimens of plants and animals to Aristotle.

Aristotle led the school for twelve years, but eventually ran into political difficulties. His relationship with Alexander was disturbed and an anti-Macedonian attitude had arisen in Athens. King Philip had submitted to the Greek city-states and Alexander maintained this after the death of his father. Aristotle was considered a friend of Alexander in Athens and even, like Socrates, was charged with wickedness. Aristotle said that the Athenians were not allowed to sin a second time against philosophy and fled to Chalcis, where he died a year later.

Influence

With his writings, Aristotle has exerted much influence in all kinds of areas. He is thus seen as one of the founders of logic, among other things by his concept of syllogism (a form of reasoning). Through his large-scale research into plants and animals, he can also be seen as one of the founders of biology. His book the Poetics is a standard work in the field of art in which he writes about the demands of unity and coherence, plot phases and the famous concept of catharsis (a kind of emotional cleansing).

The Ethica Nicomachea and the related Politica have for centuries been the standard works in the field of ethics and state theory. In the Middle Ages, many philosophers wrote commentaries on the work of Aristotle, including Thomas Aquinas. This genre is also called scholasticism. The thinker was so well-known that he was simply referred to as “the philosopher” in the literature of that time.

Category seen by Kant

In modern philosophy, the character of the categories was substantially revised by Kant. He was of the opinion that the old categories were not systematically determined and that the list was not exhaustive.

He first made the analytical distinction that things can be expressed in two different ways (we can approach them empirically and rationally; see also his transcendental philosophy) and, for the sake of the purity of the conceptual framework he uses; he limited himself to the determination of what categories were up to the strictly rational part. He then constructed a new list based on the four types of fundamental judgments that were already distinguished in classical logic, while applying a three-way division to each of these four possibilities. Thus, within his idealistic and transcendental philosophy, he obtained twelve categories that must be regarded as the fundamental (that means: not dependent on empiricism) forms of human judgment about reality.

Category and causality

After David Hume demonstrated with razor-sharp logic that the existence of causality cannot be proven, Kant made an attempt to save causality from Hume’s skepticism, and thereby also save the value of, for example, the physics of Isaac Newton, which had no value without the concept of causality.

Kant states that we can reason in cause-effect relationships, and he comes to this by stating that man inherently has a number of categories that are a priori and cannot be deduced from experience. One of these categories is causality.

These categories are also the necessary conditions for obtaining knowledge. Sensory stimuli are automatically colored by the categories. For example, time and space and quantity: every sensory perception assumes that it takes place in time and space. For example, if I say “look, there is a car driving”, this already assumes a quantity: namely a car. This cannot be deduced from the senses and these categories determine the conditions for the possibility of sensory knowledge.

A metaphor can clarify this. A tape recorder can only record sound, so it has a category to record sounds, but it cannot record images. This tape recorder therefore only knows part of reality, due to the fact that it only has that one form. This is also the case with humans, according to Kant: we have to look at what forms people have in order to order reality. Man may have more categories or forms than a tape recorder, but the part of reality that we can know also depends entirely on the categories that we possess.

Because Kant allowed the transcendental categories to function as a possibility for knowledge and also supported this with razor-sharp logic, he succeeded in saving the concept of causality of ruin threatened by Hume’s logic, according to some.