Historical overview of the Development of Thinking and

Modern World Conceptions over the last 2.500 years

Part 1

My attempt to explain how man came from the Greek ideals “Man

Know Thyself” to statistics today

Robert Gorter, MD, PhD.

October 17 th , 2021

Silver tetradrachm coin at the Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon depicting the Owl of Athena (circa 480–420 BC). The inscription “ΑΘΕ” is an abbreviation of ΑΘΗΝΑΙΩΝ, which may be translated as “of the Athenians”. In daily use the Athenian drachmas were called glaukes (γλαῦκες, owls). This silver coin was first issued in 479 BC in Athens after the Persians were defeated by the Greeks. In Greek mythology, a little owl (Athene noctua) traditionally represents or accompanies Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom, or Minerva, her syncretic incarnation in Roman mythology. Because of such association, the bird – often referred to as the “owl of Athena” or the “owl of Minerva” – has been used as a symbol of knowledge, wisdom, perspicacity and erudition throughout the Western world till today.

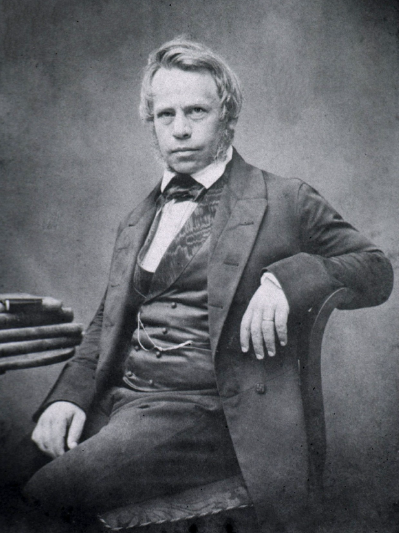

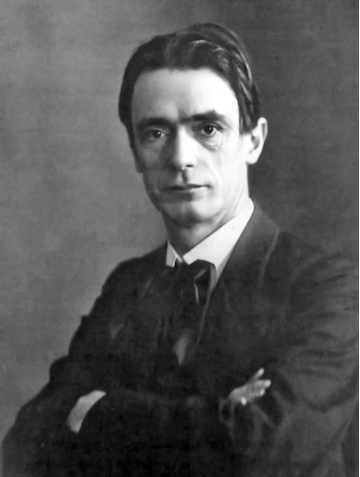

It is of great importance, that one develops a “historic consciousness” in regard to the progress of human thinking and the resulting world conceptions, which influence the way one thinks and acts today. Also, to understand the way medicine is practised today, an overview of the development of thinking is of extreme importance. Therefore, in this chapter, we will follow and summarize Rudolf Steiner’s reflections, presented in his book, ”Riddles of Philosophy”, and receive an overview of his mode of thought.

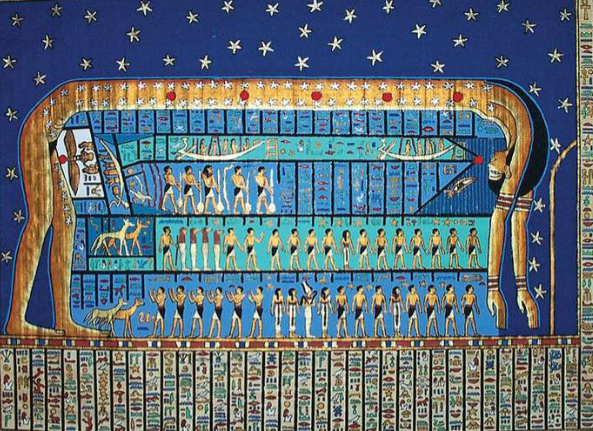

The world conception of the Greek Thinkers

With Pherekydes of Syros, who lived in the sixth century B.C., a personality appears in the Greek intellectual-spiritual life in which one can observe the birth of what will be called in the following presentation. “a world and life conception”. What he has to say about the problems of the world is, on the one hand, still like the mystical symbolic accounts of a time that lies before the striving for a scientific world conception; on the other hand, his imagination penetrates through the picture, through the myth, to a form o reflection that warrants to pierce the problems of man’s existence and of his position in the world by means of a winged oak around which Zeus wraps the surface land, oceans, rivers, etc., like a woven texture. He thinks of the world as permeated by spiritual beings of which the Greek mythology speaks.

But Pherekydes also speaks of three principles (Trinity) of the world: of Chronos, of Zeus and of Chthon. Through the history of philosophy there has been much discussion as to what is to be understood by these three principles. As the historical sources on the question of what Pherekydes meant to say in his work, Heptamychos, are contradictory, it is quite understandable that the present-day opinions also do not agree. If one reflects on the traditional accounts of Pherekydes, we get the impression that we can really observe in him the beginning of philosophical thought, but that this observation is difficult because his words have to be taken in a sense that is remote from the thought habits of the present time; its real meaning is yet to be determined.

Pherekydes arrives at his world picture in a different way from that of his predecessors. The significant fact is that he feels man to be a living soul in a way different from earlier times. For the earlier world view, the word, “soul” did not yet have the meaning that it acquired in later conceptions of life, nor did Pherekydes have the idea of the soul in the sense of later thinkers.

He simply feels the soul-element of man, whereas the later thinkers want to speak clearly about it (in the form of thought), and they attempt to characterize it in intellectual terms. Men of earlier times do not as yet separate their own soul experience from the life of nature. They experience themselves in nature as they experience lightning and thunder in it, the drifting of the clouds, the course of the stars or the growth of plants. What moves one’s hand on one’s own body, what places his foot on the ground and makes him walk, for the prehistoric man, belongs to the same sphere of world forces that also causes lightning, cloud formations and all other external events. What he at this stage feels, can be expressed by saying:

“Something causes lightning, thunder, rain, moves my hand, makes my foot step, moves the air of my breath within me, turns my head”. If one expresses what is in this way experienced, one has to use words that at first hearing seem to be exaggerated. But only through these exaggerations will it be possible to understand what is intended to be conveyed.

A man who holds a world picture as it is meant here, experiences in the rain that falls to the ground the action of a force that we at the present time must call “spiritual” and that he feels to be of the same kind as the force he experiences when he is about to exert a personal activity of some kind or other. It should be of interest that this view can be found again in Goethe in his younger years, naturally in a shade of thought that it must assume in a personality of the eighteenth century. We can read in Goethe’s essay, Nature:

“She (nature) has placed me in life; she will also lead me out of it. I trust myself into her care. She may hold sway over me. She will not hate her work. It was not I who spoke about her. Nay, what is true and what is false; everything has been spoken by her. Everything is her fault, everything her merit.”

To speak as Goethe speaks here is only then possible if one feels one’s own being imbedded in nature as a whole and then expresses this feeling in thoughtful reflection. As Goethe thought, so man of an earlier time felt without transforming his soul experience into the element of thought. He did not as of yet experience thought; instead of thought there unfolded within his soul a symbolic image. The observation of the evolution of mankind leads back to a time in which thought-like experiences had not yet come into being but in which the symbolic picture rose in the soul of man when he contemplated

the events of the world. Thought life is born in man at a definite time. It causes the extinction of the previous form of consciousness in which the world is experienced in pictures.

For the thought habits of our time it seems acceptable to imagine that man, in archaic times, had observed natural elements, like wind and weather, the growth of seeds, the course of the stars, etc., and then poetically invented spiritual beings as the active creators of these events. It is, however, far from the contemporary mode of thinking to recognize the possibility that man in older times experienced those pictures as he later experienced thought, that is, as an inner reality of his soul life.

One will gradually come to recognize that in the course of the evolution of mankind a transformation of the human organization has taken place. There was a time when the subtle organs of human nature, which make possible the development of an independent thought life, had not yet been formed. In this time man had, instead, organs that represented for him what he experienced in the world of pictures.

As this gradually comes to be understood, a new light will fall on the significance of mythology on the one hand, and that of poetic production and thought life on the other. When the independent inner thought experience began, it brought the picture – consciousness to extinction. Thought emerged as the tool of truth.

This is only one branch of what survived of the old picture – consciousness that had found its expression in the ancient myth. In another branch the extinguished picture-consciousness continued to live on, if only as a pale shadow of its former existence, in the creations of fantasy and poetic imagination. Poetic fantasy and the intellectual view of the world are the two children of one mother, the old picture-consciousness that must not be confused with the consciousness of poetic imagination.

The essential process that is to be understood is the transformation of the more delicate (physiologic) organization of man. It causes the beginning of thought life. In art and poetry thought as such naturally does not have an effect. Here, the picture continues to exert its influence, but it has now a different relation to the human soul from the one it had when it also served in a cognitive function. As thought itself, the new form of consciousness appears only in the newly emerging philosophy. The other branches of human life are correspondingly transformed in a different way when thought begins to rule in the field of human knowledge.

The progress in human evolution that is characterized by this process is connected with the fact that man from the beginning of thought experience had to feel himself in a much more pronounced way than before, as a separated entity, as a “soul”. In myth the picture was experienced in such a way that one felt it to be in the external world as a reality. One experienced this reality at the same time, and one was united with it. With thought, as well as with the poetic picture, man felt himself separated from nature. Engaged in thought experience, man felt himself as an entity that could not experience nature with the same intimacy as he felt when at one with thought. More and more, the definite feeling of the contrast of nature and soul came into being.

In the civilizations of the different peoples this transition from the old picture-consciousness to the consciousness of thought experience took place at different times. In Greece we can intimately observe this transition if we focus our attention on the personality of Pherekydes of Syros. He lived in a world in which picture-consciousness and thought experience still had an equal share. His three principal ideas, Zeus, Chronos and Chthon, can only

be understood in such a way that the soul, in experiencing them, feels itself as belonging to the events of the external world. One is dealing here with three inwardly experienced pictures and one finds access to them only when one does not allow himself to be distracted by anything that the thought habits of present times are likely to imagine as their meaning.

Chronos is not time as one thinks of it today. Chronos is a being that in contemporary language can be called “spiritual” if one keeps in

mind that one does not thereby exhaust its meaning. Chronos is a live and its activity is the devouring, the consumption of the life of

another being, Chthon. Chronos rules in nature; Chronos rules in man;

in nature and in man Chronos consumes Chthon. It is of no importance whether one considers the consumption of Chthon through Chronos as inwardly experienced or as external events. Zeus is connected with these two beings. In the meaning of Pherekydes one must no more think of Zeus as a deity in the sense of the present day conception of mythology, than as of mere “space” in its present sense, although he is the being through whom the events that go on between Chronos and Chthon are transformed into spatial, extended form.

The cooperation of Chronos, Chthon and Zeus is felt directly as a picture content in the sense of Pherekydes, just as much as one is aware of the idea that one is eating, but is also experienced as something in the external world, like the conception of the colors blue or red. We turn our attention to fire as it consumes its fuel.

Chronos lives in the activity of fire, of warmth. Whoever regards fire in its activity and keeps himself under the effect, not of independent thought but of image content, looks at Chronos. In the activity of fire, not in the sensually perceived fire, he experiences time simultaneously. Another conception of time does not exist before the birth of thought. What is called “time” in the present age is an idea that has been developed only in the age of

intellectual world conception.

If one turns his attention to water, not as it is as water but as it changes into air or vapor, or to clouds that are in the process of dissolving, one experiences as image content the force of Zeus, the spatially active “spreader”. One could also say, the force of centrifugal extension. If one looks on water as it becomes solid, or on the solid as it changes into fluid, we are watching Chthon. Chthon is something that later in the age of thought-ruled world conception becomes “matter”, the stuff “things are made of”; Zeus has become “space”, Chronos changes into “time”.

In the view of Pherekydes the world is constituted through the co-operation of these three principles. Through the combination of their actions the material world of sense perception, fire, air, water and earth, come into existence on the one hand, and on the other, a certain number of invisible supersensible spirit beings who animate the four material worlds. Zeus, Chronos and Chthon could be referred to as “spirit”, ”soul” and “matter”, but their significance is only approximated by these terms. It is only through the fusion of these three original beings that the more material realms of the world of fire, air, water and earth, and the more soul-like and spirit- like (supersensible) beings come into existence. Using expressions of later world conceptions, one can call Zeus, space-creator; Chronos, time-creator; Chthon, matter-producer, the three “mothers of the world origin”. We can still catch a glimpse of them in Goethe’s Faust, in the scene of the second part, where Faust sets out on his journey to the “mothers”.

Connected with the birth of thought life is the shattering of the foundation of the inner feelings of the soul. This inner experience should not be over-looked in a consideration of the time when the intellectual world conception began. One could not have felt this beginning as progress if one had not believed that with thought one took possession of something that was more perfect than the old form of image experience. Of course, at this stage of thought development, this feeling was not clearly expressed. But what one now, in retrospect, can clearly state with regard to the ancient Greek thinkers was then merely felt. They felt that the pictures that were experienced by their immediate ancestors did not lead to the highest, most perfect, original, causes. In these pictures only the less perfect causes were revealed; one must raise one’s thoughts to still higher causes from which the content of those pictures is merely derived.

Through progress into the thought life, the world was now conceived as divided into a more natural and a more spiritual sphere. The basis

for the much later dualistic world concept was laid.

Pherekydes found harmony in his surroundings that lies at the bottom of all phenomena and is manifested in the motions of the stars, in the course of the seasons with their blessings of thriving plant life, etc. In this beneficial course of things, harmful, destructive powers intervene, as expressed in the pernicious effects of the weather, earthquakes, etc. In observing all this, one can be lead to a realization of a dualism in the ruling powers, but the human

soul must assume an underlying unity. It naturally feels that, in the last analysis, the ravaging hail, the destructive earthquake, must spring from the same source as the beneficial cycle of the seasons.

In this fashion man looks through good and evil and sees behind it an original good. The same good force rules in the earthquake as in the blessed rain of spring. In the scorching, devastating heat of the sun the same element is at work that ripens the seed. The “Good Mothers of all origin” are, then, in the pernicious events also. When man experiences this feeling, a powerful world riddle emerges before the soul. To find the solution, Pherekydes turns toward his Ophioneus. As Pherekydes leans on the old picture conception, Ophioneus appears to him as a kind “world serpent”. It is in reality a

spirit being, which, like all other beings of the world, belongs to the children of Chronos, Zeus and Chthon, but that has later so changed that its effects are directed against those of the “Good Mother of origin”. Thus, the world is divided into three parts. The first part consists of the “Mothers”, which are presented as good, as perfect; the second part contains the beneficial world events; the third part, the destructive or only imperfect world processes that, as Ophioneus, are intertwined in the beneficial effects. For Pherekydes, Ophioneus is not merely a symbolic idea for the detrimental destructive world forces. Pherekydes stands with his conceptive imagination at the borderline between picture and thought. He does not think that there are devastating powers that he conceives in the pictures of Ophioneus, nor does such a thought process develop in him as an activity of fantasy. Rather, he looks on

the detrimental forces, and immediately Ophioneus stands before his soul as the red color stands before our souls when we look at a rose.

Whoever sees the world only as it presents itself to image perception does not, at first, distinguish in his thought between the events of the “Good Mothers” and those of Phioneus. At the borderline of a thought-formed world conception, the necessity of this distinction is felt for only at this stage of progress does the soul feel itself to be a separate, independent entity. It feels the necessity to ask what is the origin is. It must find its origin in the

depths of the world where Chronos, Zeus and chthon had not as yet found their antagonists. But the soul also feels that it cannot know anything of its own origin at first, because it sees itself in the midst of a world in which the “Mothers” work in conjunction with Ophioneus. It feels itself in a world in which the perfect and the imperfect are joined together. Ophioneus is twisted into the soul’s own being. One can feel what went on in the souls of individual personalities of the sixth century B.C. if one allows the feelings described here to make a sufficient impression on oneself. With

ancient mythical deities such souls felt themselves woven into the imperfect world. The deities belonged to the same imperfect world

as they did themselves.

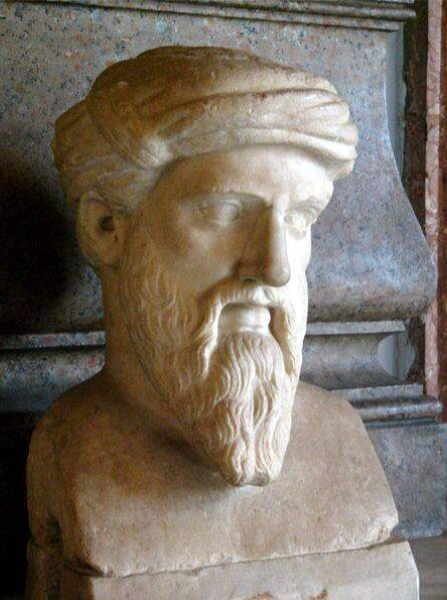

The spiritual brotherhood, which was founded by Pythagoras of Samos between 549 and 500 B.C. in Kroton in Magna Graecia, grew out of such a mood. Pythagoras intended to lead his followers back to the experience of the “Good Mothers”, in which the origin of their souls was to be found. It can be said in this respect that he and his disciples meant to serve “other gods” than those of the people. With this fact something was given that must appear as a break between spirits like Pythagoras and the people, who were satisfied with their gods. Pythagoras considered these gods as belonging to the realm of

the imperfect. In this difference one can also find the reason for the “secret” that is often referred to in connection with Pythagoras and that was not to be betrayed to the uninitiated. It consisted in the fact that Pythagoras had to attribute to the human soul an origin different from that of the gods of the popular religion.

In the picture of Pythagoras, present-day thinking also feels the idea of the so-called “transmigration of souls” as a disturbing factor. It is even felt to be naïve that Pythagoras is reported to have said that he knew that he had already been on earth in an earlier time as another human being. It may be recalled that that great representative of modern enlightenment, Lessing, in his Education of the Human Race, renewed this idea of man’s repeated lives on earth out of a mode of thinking that was entirely different from that of Pythagoras. Lessing could conceive the progress of the human race only in such a way that the human souls participated repeatedly in the life of the successive great phases of history.

The idea of reincarnation is present in Pythagoras, but it would be erroneous to believe that he, along with Pherekydes, who is mentioned as his teacher in antiquity, has yielded to this idea because he had, by means of a logical conclusion, arrived at the thought that the path of development indicated above could only be reached in repeated earthly lives. To attribute such an intellectual mode of thinking to Pythagoras would be to misjudge him. We are

told of his extensive journeys. We hear that he met together with wise men who had preserved traditions of oldest human insight.

When we observe the oldest human conceptions that have come down to us through posterity, we arrive at the view that the idea of

repeated lives on earth was widespread in remote antiquity.

Pythagoras took up the thread from the oldest teachings of humanity. The mythical teachings in picture form appeared to him as deteriorated conceptions that had their origin in older and superior insights. These picture doctrines were to change in his time into thought-formed world conception, but this intellectual world conception appeared to him as only a part of the soul’s life. This part had to be developed to greater depths. It could then lead the soul to its origins. By penetrating in this direction, however, the soul discovers in its inner experience the repeated lives on earth as a soul perception. It does not reach its origins unless it finds its way through the repeated terrestrial lives. As a wanderer, walking to a distant place, naturally passes through other places on his path, so the soul on its path to the “Mothers” passes the preceding lives through which it has gone during its descent from its former existence in perfection, to its present life in imperfection. If one considers everything that is pertinent in this problem, the inference is inescapable that the view of repeated earth lives is to be attributed to Pythagoras in this sense as his inner perception, not as something that was arrived at through a process of conceptual conclusion.

Let us think Pythagoras as standing before the beginning of intellectual world conception. He saw how thought took its origin in the soul that had, starting from the “Mothers”, descended through mere thought. He had to seek the highest knowledge in a sphere in which thought was not yet at home. There he found a life of the soul that was beyond thought life. As the soul experiences proportional numbers in the sound of music, so Pythagoras developed a soul life in which he knew himself as living in a connection with the world that can be intellectually expressed in terms of numbers. But for what is thus experienced, these numbers have no other significance than the physicist’s proportional tone numbers have for the experience of music.

For Pythagoras the mythical gods must be replaced by thought. At the same time, he develops an appropriate deepening of the soul life; the soul, which through thought has separated itself from the world, finds itself at one with the world again. It experiences itself as not separated from the world. This does not take place in a region in which the world-participating experience turns into a mythical picture, but in a region in which the soul reverberates with the invisible, sensually imperceptible cosmic harmonies. It brings into awareness, not its own thought intentions, but what cosmic powers

exert as their will, thus allowing it to become conception in the soul of man.

In Pherekydes and Pythagoras the process of how thought- experience world conception originates in the human soul is revealed. Working themselves free from the older forms of conception, these men arrive at an inwardly independent conception of the “soul” distinct from external “nature”. What is apparent in these two personalities, the process in which the soul wrests its way out of the old picture conceptions, takes place more in the undercurrents of the souls of the other thinkers with whom it is customary to begin the account of the development of Greek philosophy. The thinkers

who are ordinarily mentioned first are Thales of Miletos (640-550 B.C.), Anaximander (born 610 B.C.), Anaximenes (flourished 600 B.C.)

and Heraclitus (born 500 B.C. at Ephesus).

Whoever acknowledges the preceding arguments to be justified will also find a presentation of these men admissible that must differ from the usual historical accounts of philosophy. Such accounts are, after all, always based on the unexpressed presumption that these men had arrived at their traditionally reported statements through an imperfect observation of nature. Thus, the statement is made that the fundamental and original being of all things was to be found in “water”, according to Thales; in the “infinite”, according to Anaximander; in “air”, according to Anaximenes; in “fire”, in the

opinion of Heraclitus.

The thinkers mentioned so far are succeeded historically by Xenophanes of Kolophon (born 570 B.C.), Parmenides (born 460 B.C., living as a teacher in Athens), Zenon of Elea (who reached his peak around 500 B.C.) and Melissos of Samos (about 450 B.C.).

The thought element is already alive to such a degree in these thinkers, that they demand a world conception in which the life of thought is fully satisfied; they recognize truth only in this form. How must the world ground be constituted so that it can be fully absorbed within thinking? This is their question.

Xenophanes finds that the popular gods cannot stand the test of thought; therefore, he rejects them. His god must be capable of being thought. What the senses perceive is changeable, is burdened with qualities not appropriate to thought, whose function it is to seek what is permanent. Therefore, God is the unchangeable, eternal unity of all things to be seized in thought.

Parmenides sees the Untrue, the Deceiving, in sense-perceived, external nature. He sees what alone is true in the Unity, the Imperishable that is seized by thought.

Zeno tries to come to terms with it, and do justice to, the thought experience by pointing out in the change of things, in the process of becoming, in the multiplicity that is shown by the external world. One of the contradictions pointed out by Zeno is, that the fastest runner (Achilles) could not catch up with a turtle, for no matter how slowly it moved, the moment Achilles arrived at the point it had just occupied, it would have moved on a little. Through such contradictions Zeno intimates how a conceptual imagination that leans on the external world is caught in self-contradiction. He points to the difficulty such thought meets when it attempts to find the truth. According to a Dialogue of Plato, the young Socrates is told by Parmenides that he should learn the “art of thought” from Zeno; otherwise, truth would be unattainable for him. This “art of thought” was felt to be a necessity for the human soul intending to approach the spiritual fundamental grounds of existence.

Thus, the time of picture experiences came to an end with the beginning of thought life in the ancient, pre-Christian, Greek philosophers. Thought formed a wall around the human soul, so to speak. And the entire panorama of the picture experiences was now extinguished. The soul could experience itself in the surroundings of space and time only if it united itself with thought.

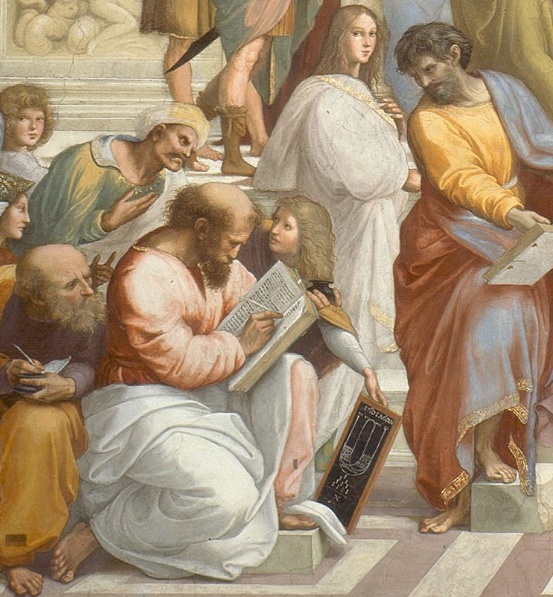

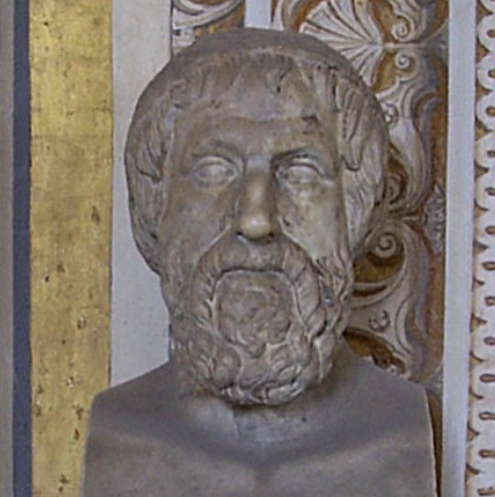

Plato, who was born in Athens in 427 B.C., felt, as a disciple of Socrates that his master had helped to consolidate his confidence in the life of thought. What the entire previous development tended to bring into appearance reaches a climax in Plato. This is the conception that in thought life the world sprit reveals itself. The awareness of this conception sheds, to begin with, its light over all of Plato’s soul life. Nothing that man knows through the senses or otherwise, has any value as long as the soul has not exposed it to the light of thought. Philosophy becomes for Plato the science of ideas as the world of true being, and the idea is the manifestation of the world spirit through the revelation of thought. The light of the world spirit shines into the soul of man and reveals itself there in the form of ideas; the human soul, in seizing the idea, unites itself with the force of the world spirit. The world that is spread in space and time is like the mass of the ocean water in which the stars are reflected, but what is real is only reflected as idea. Thus, for Plato, the whole world changes into ideas that act upon each other. Their effect in the world is produced through the fact that the ideas are reflected in hyle, the original matter. What one sees as the many individual things and events comes to pass through this reflection. One does not need extend knowledge to hyle, the original matter however, for in it there is no truth. One reaches truth only if we strip the world picture of everything that is not idea. For Plato, the human soul is living in the idea, but this life is so constituted that the soul is not a manifestation of its life in the ideas in all its utterances. Insofar as it is submerged in the life of ideas, it appears as the “rational soul” (thought-bearing soul), and as such, the soul appears to itself when it becomes aware of itself in thought perception. It must also manifest in such a way that it appears as the “non-rational soul” (not-thought bearing soul). As such, it again appears in a twofold way as courage-developing, and as appetitive soul. Thus, Plato seems to distinguish three members or parts in the human soul: The rational soul, the courage-like (or will-exertive) soul and the appetitive soul. One should, however, describe the spirit of his conceptional approach better if one expresses it in a different way. According to its nature, the soul is a member of the world of ideas, but it acts in such a way that it adds an activity to its life in reason through its courage life and its appetitive life. In this threefold mode of utterance it appears as earthbound soul. It descends as a rational soul through physical birth into a terrestrial existence, and with death again enters the world of ideas. Insofar as it is rational soul, it is immortal, for as such it shares with its life the eternal existence of the world of ideas.

Plato’s doctrine of the human soul emerges as a significant fact in the age of thought perception. The awakened thought directed man’s attention toward the soul. A perception of the soul develops in Plato that is entirely the result of thought perception. Thought in Plato has become bold enough not only to point toward the soul but to express what the soul is, as it were, to describe it. What thought has to say about the soul gives it the force to know itself in the eternal. Indeed, thought in the soul even sheds light on the nature of the temporal by expanding its own being beyond this temporal existence. The soul perceives thought. As the soul appears in its terrestrial life, it could not produce in itself the pure form of thought. Where does the thought experience come from if it cannot be developed in the life on earth? It represents a reminiscence of a pre-terrestrial, purely spiritual state of being. Thought has seized the soul in such a way that it is not satisfied by the soul’s terrestrial form of existence. It has been revealed to the soul in an earlier state of being (pre-existence) in the spirit world (world of ideas) and the soul recalls it during its terrestrial existence through the reminiscence of the life it has spent in the spirit.

What Plato has to say about the moral life follows from this soul conception? The soul is moral if is so arranges life that it exerts itself to the largest possible measure as rational soul. Wisdom is the virtue that stems from the rational soul; it ennobles human life. Fortitude is the virtue of the will-exertive soul; Temperance is that of the appetitive soul. These virtues come to pass when the rational soul becomes the ruler over the other manifestations of the soul. When all three virtues harmoniously act together, there emerges what Plato calls, Justice, the direction toward the Good, Dikaiosyne.

Plato’s most famous disciple, Aristotle (born 384 B.C. in Stageira, Thracia, died 321 B.C.), together with his teacher, represents a climax in Greek thinking. With him, the process of the absorption of thought life into the world conception has been completed and come to rest. Thought takes its rightful possession of its function to comprehend, out of its won resources, the being and the events of the world. With Aristotle, this authority has to become a matter of course. It is now a question of confirming it everywhere in the various fields of knowledge. Aristotle understands how to use thought as a tool that penetrates into the essence of things. For Plato, it had been the task to overcome the thing or being of the external world. When it has been overcome, the soul carries in itself the idea of which the external being had only been overshadowed, but which had been foreign to it, hovering over it in a spiritual world of truth.

Aristotle intends to submerge into the beings and events, and what the soul finds in this submersion, it accepts as the essence of the thing itself. The soul feels as if it had only lifted this essence out of the thing and as if it had brought this essence for its own consumption into the thought form in order to be able to carry it in itself as a reminder of the thing. To Aristotle’s mind, the ideas are in the things and the events. They are the side of the things through which these things have a foundation of their own in the underlying material, matter (hyle).

Plato, like Aristotle, lets his conception of soul shed its light on his entire world conception. In both thinkers one can describe the fundamental constitution of their philosophy as a whole if one succeeds in determining the basic characteristics of their soul conceptions. To be sure, for both of them many detailed studies would have to be considered that cannot be attempted in this course. But the direction their mode of conception took is, for both, indicated in their soul conceptions.

Plato is concerned with what lives in the soul and, as such, shares in the spirit world. What is important for Aristotle is the question of how the soul presents itself for man in his own knowledge. As it does with other things, the soul must also submerge into itself in order to find what constitutes its own essence. The idea, which, according to Aristotle, man finds in a thing outside his soul, is the essence of the thing, but the soul has brought this essence into the form of an idea in order to have it for itself. The idea does not have its reality in the cognitive soul but in the external thing in connection with its material life (hyle). If the soul submerges into itself, however, it finds the idea as such in reality. The soul in this essence is idea, but active idea, an entity exerting action, and it behaves also in the life of man as such an active entity. In the process of germination of man it lays hold upon material existence.

Aristotle is the thinker who has brought thought to the point where it unfolds to a world conception through its contact with the essence of the world. The age before Aristotle led to the experience of thought; Aristotle seizes the thoughts and applies them to whatever he finds in the world. The natural way, peculiar for Aristotle, in which he lives in thought as a matter of course, leads him to investigate logic, the laws of thought itself. Such a science could only come into being after the awakened thought had reached a stage of great maturity and of such a harmonious relationship to the things of the outer world as one can find it in Aristotle.

Aristotle’s Ten Categories

Aristotle’s Categories is a singularly most important work of philosophy. It not only presents the backbone of Aristotle’s own philosophical theorizing but has exerted an unparalleled influence on the systems of many of the greatest philosophers in the western tradition. The set of doctrines in the Categories, which I will henceforth call categorialism, provides the framework of inquiry for a wide variety of Aristotle’s philosophical investigations, ranging from his discussions of time and change in the Physics to the science of being qua being in the Metaphysics, and even extending to his rejection of Platonic ethics in the Nicomachean Ethics. Looking beyond his own works, Aristotle’s categorialism has engaged the attention of such diverse philosophers as Plotinus, Porphyry, Aquinas, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Kant, Hegel, Brentano, and Heidegger (to mention just a few), who have variously embraced, defended, modified or rejected its central contentions. All, in their different ways, have thought it necessary to come to terms with features of Aristotle’s categorical scheme.

Plainly, the enterprise of categorialism inaugurated by Aristotle runs deep in the philosophical psyche. Even so, despite its wide-reaching influence — and, indeed owing to that influence — any attempt to describe categorialism faces a significant difficulty: experts disagree on many of its most important and fundamental aspects.

But all agree that the 10 Categories formulated by Aristotle laid the basis for modern thinking and Natural Sciences.

Thought Life in the beginning of the Christian Era

In the age that follows the flowering of Greek world conceptions, philosophy submerges into religious life. The philosophical trends vanish, so to speak, into religious currents and emerge only later. It is not meant to imply by this statement that these religious movements have no connection with the development of the philosophical life. On the contrary, this connection exists in the most extensive measure. Here, however, no statement about the evolution of religious life is intended, but rather a characterization of the development of the world conceptions insofar as it results from thought experience as such.

After the exhaustion of Greek thought life, an age begins in the spiritual life of mankind in which the religious impulses become the driving forces of the intellectual world conceptions as well. For Plotinus, his own mystical experience was the source of inspiration of his ideas. A similar role for the spiritual development of mankind in its general life is played by the religious impulses in an age that begins with the exhaustion of Greek philosophy until John Scotus Erigena (died 885 A.D.).

The development of thought does not completely cease in this age. One even witnesses the unfolding of magnificent and comprehensive thought structures. The thought energies, however, do not have their source within themselves bur are derived from religious impulses.

The religious mode of conception in this period flows through the developing human souls and the resulting world pictures are derived from this stimulation. The thoughts that occur in this process are Greek thoughts that are still exerting their influence. They are adopted and transformed, but are not brought to new growth out of themselves. The world conceptions emerge out of the background of the religious life. What is alive in them is not self-unfolding thought, but the religious impulses that are striving to manifest themselves in the previously conquered thought forms.

One can study this development in several significant phenomena. One can see Platonic and older philosophies engaged on European soil in the endeavor to comprehend or to contradict what the religions spread as their doctrines. Important thinkers attempt to present the revelation of religion as fully justified before the forum of the old world conceptions.

What is historically known as Gnosticism develops in this way in a more Christian or a more pagan coloring. Personalities of significance of this movement are Valentinus, Basilides and Marcion. Their thought creation is a comprehensive conception of world evolution. Cognition, gnosis, when it rises from the intellectual to the trans-intellectual realm, leads into the conception of a higher world-creative entity. This being is infinitely superior to everything seen as the world by man, and so are the other lofty beings it produces out of itself, the aeons. They form a descending series of generations in such a way that a less perfect aeon always proceeds from a more perfect one. As such, in a later stage of evolution an aeon has to be considered to be also the creator of the world that is visible to man and to which man himself belongs. Into this world as aeon of the highest degree of perfection now can join. It is an aeon that has remained in a purely spiritual, perfect world and has there continued its development.

The Gnostics, who were inclined toward Christianity, saw in Christ Jesus the perfect aeon, which has united with the terrestrial world.

Personalities like Clemens of Alexandria (died ca. 211 A.D.) and Origen (born ca. 185 A.D.) stood more on a dogmatic Christian ground. Clemens accepts the Greek world conceptions as a preparation of the Christian revelation and uses them as instruments to express and defend the Christian impulses. Origen proceeds in a similar way.

One can find a thought life inspired by religious impulses flowing together in a comprehensive stream of conceptions in the writings of Dionysius the Areogagite, which are mentioned from 533 A.D. They probably had not been composed much earlier, but they do go back, not in their details but in their characteristic features, to earlier thinking of his age. Their content can be sketched in the following way. When the soul liberates itself from everything that it can perceive and think as being, when it also transcends beyond what it is capable of thinking as non-being, then it can spiritually divine the realm of the over-being, the hidden Godhead. In this entity, primordial being is united with primordial goodness and primordial beauty. Starting from this primeval trinity, the soul witnesses a descending order of beings that lead down to man in hierarchical array.

In the ninth century Scotus Erigena adopts this conception of the world and develops it in his own way. The world for him presents itself as an evolution in four forms of nature. The first of these is the creating and not created nature. In it is contained the purely spiritual primordial cause of the world out of which evolves the creating and created nature. This is the sum of purely spiritual entities and energies, which through their activity produce the created and not creating nature, to which the sensual world and man belong. They develop in such a way that they are received into the not created and not creating nature, in which the facts of salvation, the religious means of grace, etc., unfold their effect.

In those parts of Asia Minor where the conceptions of Aristotle had been spread by, among others, Alexander the Great, the tendency now arose to lend expression to the Semitic religious impulses in the ideas of the Greek thinker. This tendency was then transplanted also to European soil and so entered into the European spiritual life through such thinkers as the great Aristotalians, Averroes (1126-1198), Maimonides (1135-1204), and others.

In Averroes, one can find the view that it is an error to assume that a special thought world exists in the personality of man. There is only one homogeneous thought world in the divine primordial being. As light can be reflected in any mirrors, so also one thought world is revealed in many human beings. During human life on earth, to be sure, a further transformation of thought world takes place, but this is, in reality, only a process in the spiritually homogeneous primordial ground. With man’s death the individual revelation through him simply comes to an end. His thought life now exists only in the one thought life.

This world conception allows the Greek thought experience to continue its effect, but does it in such a way that it is now anchored in the uniform divine world ground. It leaves us with the impression of being a manifestation of the fact that the developing human soul did not feel in itself the intrinsic energy of thought. It therefore, projected this energy into an extra-human world power.

The World Conceptions of the Middle Ages

A foreshadowing of a new element produced by thought life emerges in St. Augustine (354-430). This element soon vanishes from the surface, however, to continue unnoticeably under the cover of religious conception, becoming distinctly discernible again only in the later Middle Ages. In St. Augustine, the new element appears as if it were a reminiscence of Greek thought life. He looks into the external world and into himself, and comes to the conclusion: May everything else the world reveals contain nothing but uncertainty and deception, one thing cannot be doubted, and that is the certainty of the soul’s experience itself. I do not owe this inner experience to a perception that could deceive me; I am in it myself; it is, for I am present when its being is attributed to it.

One can see a new element in these conceptions as against Greek thought life, in spite of the fact that they seem at first like a reminiscence of it. Greek thinking points toward the soul; in St. Augustine, we are directed toward the center of the life of the soul. The Greek thinkers contemplated the soul in its relation to the world; St. Augustine’s approach, something in soul life confronts this soul life and regards it as a special, self-contained world.. One can call the center of the soul life the “ego” of man. To the Greek thinkers, the relation of the soul to the world becomes problematic, to the thinkers of modern times, that of the “ego” to the soul. In St. Augustine, we have only the first indication of this situation. The ensuing philosophical currents are still too much occupied with the task of harmonizing world conception and religion to become distinctly aware of the new element that has not entered into spiritual life. But the tendency to contemplate the riddles of the world in accordance with the demand of this new element lives more or less unconsciously in the souls of the time that now follows. In thinkers like Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) and Thomas Aquinas (1227-1274), this tendency still shows itself in such a way that they attribute to self-supportive thinking the ability to investigate the processes of the world to a certain degree, but they limit this ability. There is for them a higher spiritual reality to which thinking, left to its own resources, can never attain, but that must be revealed to it in a religious way. Man is, according to Thomas Aquinas, rooted with his soul life in the reality of the world, but this soul life cannot know this reality in its full extent through itself alone. Man could not know how his own being stands in the course of the world if the spirit being, to which his knowledge does not penetrate, did not deign to reveal to him what must remain concealed to a knowledge relying on its own power alone. Thomas Aquinas constructs his world picture on this presumption. It has two parts, one of which consists of the truths that are yielded to man’s own thought experience about the natural course of things. This leads to a second part that contains what has come to the soul of man through the Bible and religious revelation. Something that the soul cannot reach by itself, if it is to feel itself in its full essence, must therefore penetrate into the soul.

Thomas Aquinas made himself thoroughly familiar with the world conception of Aristotle, who becomes, as it were, his master in the life of thought. In this respect, Thomas Aquinas is, to be sure, the most prominent, but nevertheless only one of the numerous personalities of the Middle Ages who erected their own thought structure entirely on that of Aristotle. For centuries, he is il maestro di color che sanno, the master of those who know, as Dante expresses the veneration for Aristotle in the Middle Ages. Thomas Aquinas strives to comprehend what is humanly comprehensible in Aristotelian method. In this way, Aristotle’s world conception becomes the guide to the limit to which the soul life can advance through its own power for him. Beyond these boundaries lies the realm that the Greek world conception, according to Thomas, could reach.

Therefore, human thinking for Thomas Aquinas is in need of another light by which it must be illuminated. He finds this light in revelation. Whatever was to be the attitude of the ensuing thinkers with respect to this revelation, they could no longer accept the life of thought in the manner of the Greeks. It is not sufficient to them that thinking comprehends the world; they make the presupposition that it should be possible to find a basic support for thinking itself. The tendency arises to fathom man’s relation to his soul life. Thus, man considers himself a being who exists in his soul life. If one calls this entity the ego, one can say that in modern times the consciousness of the ego is stirred up in man’s soul life in a way similar to that in which thought was born in the philosophical life of the Greeks. Whatever different forms the philosophical currents in this age assume, they all hinge on the search for the ego-entity. This fact, however, is not always brought clearly to the consciousness of the thinkers themselves. They mostly believe they are concerned with questions of a different nature. One could say that the Riddle of the Ego appears in a great variety of masks. At times it lives in the statement that this riddle is at the bottom of some view or other might appear as an arbitrary or forced opinion. In the nineteenth century this struggle over the riddle of the ego comes to its most intensive manifestation, and the world conceptions of the present time are still profoundly engaged in this struggle.

The world riddle already lived in the conflict between the nominalists and the realists in the Middle Ages. One can call Anselm of Canterbury a representative of realism. For him, the general ideas that man forms when he contemplates the world are not mere nomenclatures that the soul produces for itself, but they have their roots in a real life. In one forms the general idea “lion” in order to designate all lions with it, it is certainly correct to say that, for sense perception, only the individual lions have reality. The general concept “lion” is not, however, only a summary designation with significance only for the human mind. It is rooted in a spiritual world, and the individual lions of the world of sense perception are the various embodiments of the one lion nature expressed in the idea “lion”.

To the Greek thinker, thought came as a perception. It rose in the soul as the red color appears when a man looks at a rose, and the thinker received it as a perception. As such the thought had the immediate power of conviction. The Greek thinker had the feeling, when he placed himself with his soul receptively before the spiritual world that no incorrect thought could enter from this world into the soul just as no perception of a winged horse could come from the sense world as long as the sense organs were properly used. For the Greeks, it was a question of being able to garner thought forms from the world. They were then themselves the witness of their truth. The fact of this attitude is not contradicted by the Sophists, nor is it denied by ancient Scepticism. Both currents have an entirely different shade of meaning in antiquity from similar tendencies in modern times. They are not evidence against the fact that the Greek experienced thought in a much more elementary, content-saturated, vivid and real way that it can be experienced by modern man. This vividness, which in ancient Greece gave the character of perception to thought, is no longer to be found in the Middle Ages.

What has happened is this? As in Greek times thought entered into the human soul, extinguishing the formerly prevalent picture consciousness, so, in a similar way, during the Middle Ages the consciousness of the “ego” penetrated the human soul, and this dampened the vividness of thought. The advent of the ego-consciousness deprived thought of the strength through which it had appeared as perception. One can only understand how the philosophical life advances when one realizes how, for Plato and Aristotle, the thought, the idea, was something entirely different from what it was for the personalities of the Middle Ages and modern times. The thinker of antiquity had the feeling that thought was given to him; the thinker of the later time had the impression that he was producing thought. Thus, the inquiry into the nature of the “general ideas” begins. The thinker asks himself the questions, “What is it that I have really produced with them? Are they only rooted in me, or do they point toward a reality?”

In the period between the ancient current of philosophical life and that of modern philosophy, the source of Greek thought life is gradually exhausted. Under the surface, however, the human soul experiences the approaching ego-consciousness as a fact. Since the end of the first half of the Middle Ages, man is confronted with this process as an accomplished fact, and under the influence of this confrontation, new Riddles of Life emerge. Realism and Nominalism are symptoms of the fact that man realizes the situation. The manner in which both Realists and Nominalists speak about thought shows that, compared to its existence in the Greek soul, it has faded out, has been dampened as much as had been the old picture consciousness in the soul of the Greek thinker.

This point is the dominating element that lives in the modern world conceptions. An energy is active in them that strives beyond thought toward a new factor of reality. This tendency of modern times cannot be felt as the same that drove beyond thought in ancient times in Pythagoras and later in Plotinus. These thinkers also strove beyond thought but, according to their conception, the soul in its development, its perfection, would have to conquer the region that lies beyond thought. In modern times, it is presupposed that the factor of reality lying beyond thought must approach the soul, must be given to it from without.

In the centuries that follow the age of Nominalism and Realism, philosophical evolution turns into a search for the new reality factor. One path among those discernible to the student of this search is the one the medieval mystics, Meister Eckhardt (died 1327), Johannes Tauler (died 1361) and Heinrich Suso (died 1366) have chosen for themselves. One receives the clearest idea of this path if one inspects the so-called German Theology, written by an author historically unknown. The mystics want to receive something into the ego-consciousness; they intend to fill it with something. They therefore strive for an inner life that is “completely composed”, surrendered in tranquillity, and that thus patiently waits to experience the soul to be filled with the “Divine Ego”. In a later time, a similar soul mood with a greater spiritual momentum can be observed in Angelus Silesius (1624-1677).

A different path is chosen by Nicolaus Cusanus (1401-1464). He strives beyond intellectually attainable knowledge to a state of soul in which knowledge ceases and in which the soul meets its god in “knowing ignorance”, in docta ignorantia. Examined superficially, this aspiration is similar to that of Plotinus, but the soul constitution of these two personalities is different. Plotinus is convinced that the human soul contains more than the world of thoughts. When it develops the energy that is possesses beyond the power of thought, the soul becomes conscious of the state in which it exists, and about which it is ignorant in ordinary life.

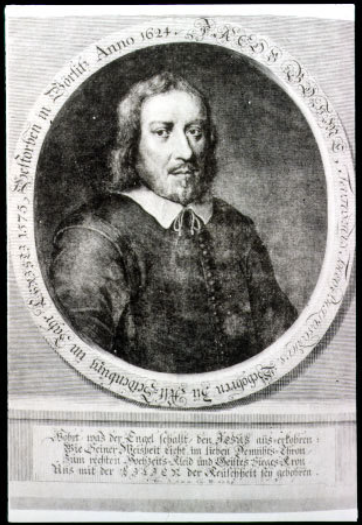

Paracelsus (1493–1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss-German physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance. He was a pioneer in several aspects of the “medical revolution” of the Renaissance, emphasizing the value of observation in combination with received wisdom. He is credited as the “father of toxicology”. Paracelsus also had a substantial impact as a prophet or diviner, his “Prognostications” being studied by Rosicrucians in the 1600s. Paracelsianism is the early modern medical movement inspired by the study of his works.

Paracelsus (1493-1541) already has the feeling with respect to nature, which becomes more and more pronounced in the modern world conception that is an effect of the soul’s feeling of desolation in its ego-consciousness. He turns his attention toward the processes of nature. As they present themselves they cannot be accepted by the soul, but neither can thought, which in Aristotle unfolded in peaceful communication with the events of nature, now be accepted as it appears in the soul. It is not perceived; it is formed in the soul. Paracelsus felt that one must not let thought itself speak; one must presuppose that something is behind the phenomena of nature that will reveal itself if one finds the right relationship to these phenomena. One must be connected with one’s “ego” by means of a factor of reality other than thought. A higher nature behind nature is what Paracelsus is looking for. His mood of soul is so constituted that he does not want to experience something in himself alone, but he means to penetrate nature’s processes with his “ego” in order to have revealed to him the spirit of these processes that are under the surface of the world of the senses. Thy mystics of antiquity meant to delve into the depths of the soul; Paracelsus set out to take steps that would lead to a contact with the roots of nature in the external world.

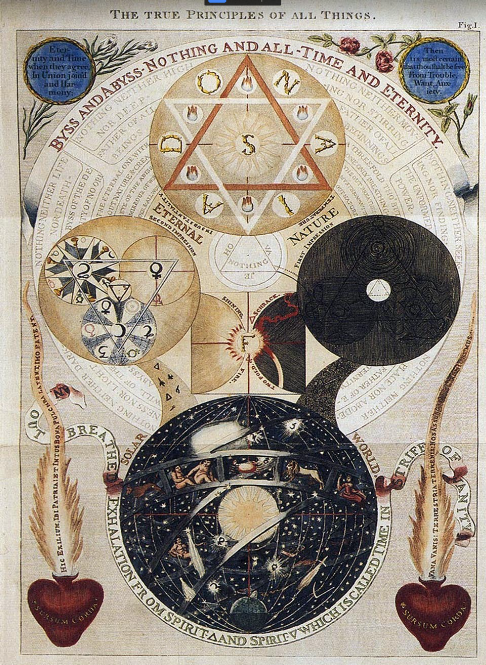

Jakob Boehme (1575-1624) who, as a lonely, persecuted craftsman, formed a world picture as though out of an inner illumination, nevertheless implants into this world picture the fundamental character of modern times. In the solitude of his soul life he develops this fundamental trait most impressively because the inner dualism of the life of the soul, the contrast between the “ego” and the other soul experiences, stands clearly before the eye of his spirit. He experiences the “ego” as it creates an inner counterpart in its own soul life, reflecting itself in the mirror of his own soul. He then finds this inner experience again in the processes of the world. “In such a contemplation one finds two qualities, a good and an evil one, which are intertwined in this world in all forces, in stars and in elements as well as in all creatures”. The evil in the world is opposed to the good as its counterpart; it is only in the evil that the good becomes aware of itself, as the “ego” becomes aware of itself in its inner soul experiences.

The World Conceptions of the Modern Age of Thought Evolution.

The rise of natural science in modern times has as its fundamental cause the same search as the mysticism of Jakob Boehme. This becomes appearent in a thinker who grew directly out of the spiritual movement, which in Copernicus (1473-1542), Kepler (1571-1630), Galileo (1564-1642), and others, led to the first great accomplishments of natural science in modern times. This thinker was Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) in Italy. When one sees how his world consists of infinitely small, animated, psychically self-aware, fundamental beings, the monads, which are uncreated and indestructible, producing in their combined activity the phenomena of nature, one could be tempted to group him with Anaxagoras, for whom the world consists of the “homoiomeries”.

Yet, there is a significant difference between these two thinkers. For Anaxagoras, the thought of the homoiomeries unfolds while he is engaged in the contemplation of the world; the world suggests these thoughts to him. Giordano Bruno feels that what lies behind the phenomena of nature must be thought of as a world picture in such a way that the entity of the ego is possible in this world picture. The ego must be a monad; otherwise, it could not be real. Thus, the assumption of the monads becomes necessary. As only the monad can be real, therefore, the truly real entities are monads with different inner qualities.

In the depths of the soul of a personality like Giordano Bruno (who reincarnated as Annie Besant), something happens that is not raised into full consciousness yet; the effect of this inner process is then the formation of the world picture. What goes on in the depths is an unconscious soul process. The ego feels that it must form such a conception of itself so that its reality is assured, and it must conceive the world in such a way that the ego can be real in it. Giordano Bruno has to form the conception of the monad in order to render possible the realization of both demands. In his thought the ego struggles for its existence in the world conception of the modern age, and the expression of this struggle is the view: I am a monad; such an entity is uncreated and indestructible.

After being convicted by the Inquisition for heresy, Giordano Bruno died by being burned alive. The personality of Giordano Bruno reincarnated as Annie Besant who played a very important role in the Theosophical Society and was the teacher of Mahatma Gandhi. She played an important role in the struggle for independence of India.

A comparison shows how different the ways are in which Aristotle and Giordano Bruno arrive at the conception of God. Aristotle contemplates the world; he surrenders to the contemplation of his evidence; at the same time, the processes of nature are for him evidence of the thought of the “first mover” of these processes. Giordano Bruno fights his way through to the conception of the monads. The processes of nature are, as it were, extinguished in the picture in which innumerable monads are presented as acting on each other; God becomes the power entity that lives actively in all monads behind the processes of the perceptible world. In Giordano Bruno’s passionate antagonism against Aristotle, the contrast between the thinker of ancient Greece and of the philosopher of modern times becomes manifest.

It becomes apparent in the modern philosophical development in a great variety of ways how the ego searches for means to experience its own reality in itself. What, in England, Francis Bacon of Verulam (1561-1626) represents in his writings has the same general character even if this does not at first sight become apparent in his endeavours in the field of philosophy. Bacon demands that the investigation of the world phenomena should begin with unbiased observation. One should then try to separate the essential from the non-essential in a phenomenon in order to arrive at a conception of whatever lies at the bottom of a thing or event. He is of the opinion that up to his times the fundamental thoughts, which were to explain the world phenomena, had been conceived first, and only thereafter were the description of the individual things and events arranged to fit these thoughts. He presupposed that the thoughts had not been taken out of the things themselves. Bacon wanted to combat this (deductive) method with his (inductive) method. The concepts are to be formed in direct contact with the things. One sees, so Bacon reasons, how an object is consumed by fire; one observes how a second object behaves with relation to fire and then observes the same process with many objects. In this fashion one arrives eventually at a conception of how things can behave with respect to fire. The fact that the investigation in former times had not proceeded in this way had, according to Bacon’s opinion, caused human conception to be dominated by so many idols instead of the true ideas about the things.

Goethe speaks about Bacon in his book on light and color in the following way:

“Bacon is like a man who is well-aware of the irregularity, insufficiency and dilapidated condition of an old building, and knows how to make this clear to the inhabitants. He advises them to abandon it, to give up the land, the materials and all appurtenances, to look for another plot, and to erect a new building. He is an excellent and persuasive speaker. He shakes a few walls. They break down and some of the inhabitants are forced to move out. He points out new building grounds; people begin to level it off, and yet it is everywhere too narrow. He submits new plans; they are not clear, not inviting. Mainly, he speaks of new unknown materials and now the world seems to be well-served. The crowd disperses in all directions and brings back an infinite variety of single items while at home, new plans, new activities and settlements occupy the citizens and absorb their attention………

If through Bacon of Verulam’s method of dispersion, natural science seemed to be forever broken up into fragments, it was soon brought to unity again by Galileo. He led natural philosophy back into the human being. When he developed the law of the pendulum and of falling bodies from the observation of swinging church lamps, he showed even in his early youth that, for the genius, one case stands for a thousand cases. In science, everything depends on the ability of becoming aware of what is really fundamental in the world of phenomena. The development of such an awareness is infinitely fruitful”.

With these words Goethe indicated distinctly the point that is characteristic of Bacon. Bacon wants to find a secure path for science because he hopes that in this way man will find a dependable relationship to the world.

René Descartes (Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; (1596–1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist. A native of the Kingdom of France, he spent about 20 years (1629–1649) of his life in the Dutch Republic after serving for a while in the Dutch States Army of Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange and the Stadtholder of the United Provinces. One of the most notable intellectual figures of the Dutch Golden Age, Descartes is also widely regarded as one of the founders of modern philosophy.

Many elements of Descartes’s philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differed from the schools on two major points: first, he rejected the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejected any appeal to final ends, divine or natural, in explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God’s act of creation. Refusing to accept the authority of previous philosophers, Descartes frequently set his views apart from the philosophers who preceded him. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, an early modern treatise on emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic “as if no one had written on these matters before.” His best known philosophical statement is “cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”; French: “Je pense, donc je suis”), found in Discourse on the Method (1637; in French and Latin) and Principles of Philosophy (1644, in Latin).

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Spinoza and Leibniz, and was later opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza, and Descartes were all well-versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well. Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes’s influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytical geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry—used in the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the Scientific Revolution.

Contrary to Bacon of Verulam, who pointed toward the bricks and the walls of the building, In Amsterdam, both Rene Descartes (1596-1650) and Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) turned their attention towards its plan. With an unbiased questioning mind Descartes (Cartesius) approaches the world, which offers him much of its riddles partly through revealed religion, partly through the observation of the senses. He now contemplates both sources in such a way that he does not simply accept and recognize as truth what either of them offers to him. Instead, he sets against the suggestions of both sources the “ego”, which answers out of its own initiative with its doubt against all revelation and against all perception. In the development of modern philosophical life, this move is a fact of the most telling significance. Amidst the world the thinker allows nothing to make an impression on his soul, but sets himself against everything with a doubt that can derive its support only from the soul itself. Now the soul apprehends itself in its own action: I doubt, that is to say, I think. Therefore, no matter how things stand with the entire world, in my doubt-exerting thinking I come to the clear awareness that I am. In this manner, Descartes arrives at his “Cogito ergo sum,” I think, therefore I am. The ego in him conquers the right to recognize its own being through the radical doubt directed against the entire world.

Descartes derives the further development of his world conception out of his root. In the “ego” he had attempted to seize existence. Whatever can justify its existence together with the ego may be considered truth. The ego finds in itself, innate to it, the idea of God. This idea presents itself to the ego as true, as distinct as the ego itself, but it is so sublime, so powerful, that the ego cannot have it through its own power. Therefore, it comes from transcendent reality to which it corresponds. Descartes believes in the reality of the external world, not because this external world presents itself as real, but because the ego must believe in itself and then subsequently in God, and because God must be thought as truthful. For it would be untrue (unfair and misleading) of God to suggest a real world to man if the latter did not exist.

It is only possible to arrive at the recognition of the reality of the ego as Descartes does through a thinking that in the most direct manner aims at the ego in order to find a point of support for the act of cognition. That is to say, this possibility can be fulfilled only through an inner activity but never through a perception from without. Any perception that comes from without gives only the qualities of extension. In this manner, Descartes arrives at the recognition of two substances in the world: One to which extension, and the other to which thinking, is to be attributed and that has its roots in the human soul. The animals, which in Descartes’ sense cannot apprehend themselves in inner self-supporting activity, are accordingly mere beings of extension, automata, and machines. The human body, too, is nothing but a machine. The soul is linked up with this machine. When the body becomes useless through being worn out or destroyed in some way, the soul abandons it to continue to live in its own element.

Descartes lives in a time in which a new impulse in the philosophical life is already discernible. The period from the beginning of the Christian era until about the time of Scotus Erigena develops in such a way, that the inner experience of thought is enlivened by a force that enters the spiritual evolution as a powerful impulse. The energy of thought as it awakened in Greece is outshone by this power. Outwardly, the progress in the life of the human soul is expressed in the religious movements and by the fact that the forces of the youthful nations of Western and Central Europe become the recipients of the effects of the older forms of thought experience. They penetrate this experience with the younger, more elementary impulses and thereby transform it. In this process one forward step in the progress in human evolution becomes evident that is caused by the fact that older and subtle traces of spiritual currents that have exhausted their vitality, but not their spiritual possibilities, are continued by youthful energies emerging from the natural spring of mankind. In such processes one will be justified in recognizing the essential laws of the evolution of mankind. They are based on rejuvenating tendencies of the spiritual life. The acquired forces of the spirit can only then continue to unfold if they are transplanted into the young, naïve, and natural energies of mankind.

The first eight centuries of the Christian era present a continuation of the thought experience in the human soul in such a way, that the new forces about to emerge are still dormant in hidden depths, but they tend to exert their formative effect on the evolution of world conception. In Descartes, these forces already show themselves at work in a high degree. In the age between Scotus Erigena and approximately the fifteenth century, thought, which in the preceding period did not openly unfold, comes again to the fore in its own force. Now, however, it emerges again from a direction quite different from that of the Greek age. With the Greek thinkers, thought is experienced as a perception. From the eighth to the fifteenth centuries it comes from out of the depths of the soul so that man has the feeling: Thought generates itself within me. In the Greek thinkers, a relation between thought and the processes of nature was still immediately established; in the age just referred to, thought stands out as the product of self-consciousness. The thinker has the feeling that he must prove thought as justified. This is the feeling of the nominalists and the realists. This is also the feeling of Thomas Aquinas, who anchors the experience of thought in religious revelations.

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries introduce a new impulse to the souls. This is slowly prepared and slowly absorbed in the life of the soul. In the field of philosophical life, this transformation becomes manifest through the fact that thought cannot now be felt as a perception, but as a product of self-consciousness. This transformation in the organization of the human soul can be observed in all fields of the development of humanity. It becomes apparent in the renaissance of art and science, and of European life, as well as in the reformatory religious movements. One will be able to discover it if one investigates the art of Dante and Shakespeare with respect to their foundations in the human soul development. Here these possibilities can only be indicated, since thus sketch is intended to deal only with the development of the intellectual world conception.

The advent of the mode of thought of modern natural science appears as another symptom of this transformation of the human soul organization. Just compare the state of the form of thinking about nature as it develops in Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler with what has preceded them. This natural scientific conception corresponds to the mood of the human soul at the beginning of the modern age in the sixteenth century. Nature is now looked at in such a way that the sense observation is now the only witness of it. Bacon is one, Galileo another personality in whom this becomes apparent. The picture of nature is no longer drawn in a manner that allows thought to be felt in it as a power revealed by nature. Out of this picture of nature, every trait that could be felt as only a product of self-consciousness gradually vanishes. Thus, the creations of self-consciousness and the observation of nature are more abruptly contrasted, separated by a gulf. From Descartes on a transformation of the soul organization becomes discernible that tends to separate the picture of nature from the creations of the self-consciousness. With the sixteenth century a new tendency in the philosophical life begins to make itself felt. While in the preceding centuries thought had played the part of an element, which, as a product of self-consciousness, demanded its justification through the world picture, since the sixteenth century it proves to be clearly and distinctly resting solely on its own ground in the self-consciousness. Previously, thought had been felt in such a manner, that the picture of nature could be considered a support for its own justification; now it becomes the task of this element of thought to uphold the claim of its validity through its own strength. The thinkers of the time that now follows feel, that in the thought experience itself something must be found, that proves this existence to be the justified creator of a world conception.

In a personality like Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), who was just as great a thinker as he was an artist, one can recognize the striving for a new law-determined picture of nature. Such spirits feel it necessary to find an access to nature not yet given to the Greek way of thinking and its after effects in the Middle Ages. Man now has to rid himself of whatever experiences he has about his own inner being if he is to find access to nature. He is permitted to depict nature only in conceptions that contain nothing of what he experiences as the effects of nature in himself.

Thus, the human soul dissociates itself from nature; it takes its stand on its ground. As long as one could think that the stream of nature contained something that was the same as what was immediately experienced in man, one could, without hesitation, feel justified to have thought bear witness to the events of nature. The picture of nature of modern times forces the human consciousness to feel itself outside nature with its thought. This consciousness further establishes validity for its thought, which is gained through its own power.

This process has been the central theme of the Germanic Mythologies: the Twilights of the Gods (German: “die Götterdämmerung”): the Gods have to withdraw from the Earth and leave Mankind alone against their divine will (but out of necessity).