In the twentieth century, when changing artistic tastes made artists like Bosch

more palatable to the European imagination, it was sometimes argued that

Bosch’s art was inspired by heretical points of view (e.g., the ideas of the

Cathars and putative Adamites) as well as by obscure hermetic practices. Again,

since Erasmus had been educated at one of the houses of the Brethren of the

Common Life in ‘sHertogenbosch, and the town was religiously progressive,

some writers have found it unsurprising that strong parallels exist between the

caustic writing of Erasmus and the often bold painting of Bosch. Although the

Brethren remained loyal to the Pope, they still saw it as their duty to denounce

the abuses and scandalous behavior of many priests: the corruption which both

Erasmus and Bosch satirized in their work.

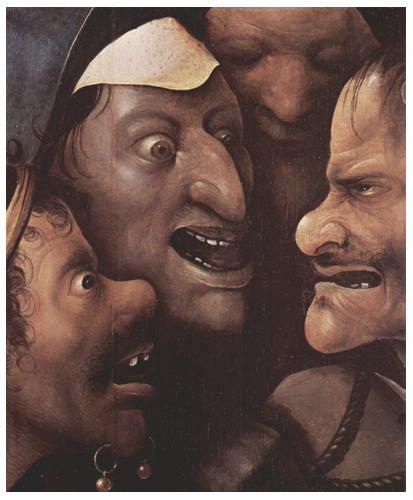

Others, following a strain of Bosch-interpretation datable already to the

sixteenth-century, continued to think his work was created merely to titillate and

amuse, much like the “grotteschi” of the Italian Renaissance. While the art of the

older masters was based in the physical world of everyday experience, Bosch

confronts his viewer with, in the words of the art historian Walter Gibson, “a world of dreams [and] nightmares in which forms seem to flicker and change before our eyes”. In one of the first known accounts of Bosch’s paintings, in 1560 the Spaniard Felipe de Guevara wrote that Bosch was regarded merely as “the inventor of monsters and chimeras”. In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch art historian Karel van Mander described Bosch’s work as comprising “wondrous and strange fantasies”; however, he concluded that the paintings are “often less pleasant than gruesome to look at”.

In recent decades, scholars have come to view Bosch’s vision as less fantastic,

and accepted that his art reflects the orthodox religious belief systems of his age.

His depictions of sinful humanity and his conceptions of Heaven and Hell are

now seen as consistent with those of late medieval didactic literature and

sermons. Most writers attach a more profound significance to his paintings than

had previously been supposed, and attempt to interpret it in terms of a late

medieval morality. It is generally accepted that Bosch’s art was created to teach

specific moral and spiritual truths in the manner of other Northern Renaissance

figures, such as the poet Robert Henryson, and that the images rendered have

precise and premeditated significance. According to Dirk Bax, Bosch’s paintings

often represent visual translations of verbal metaphors and puns drawn from

both biblical and folkloric sources.[12] However, the conflict of interpretations

that his works still elicit raise profound questions about the nature of “ambiguity”

in art of his period.

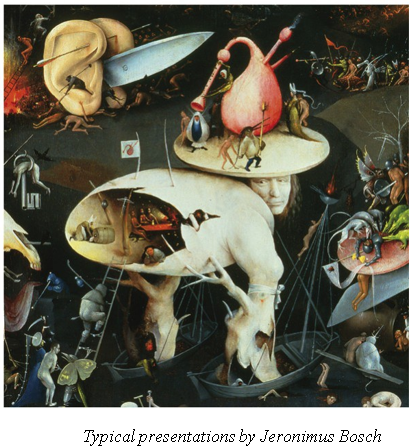

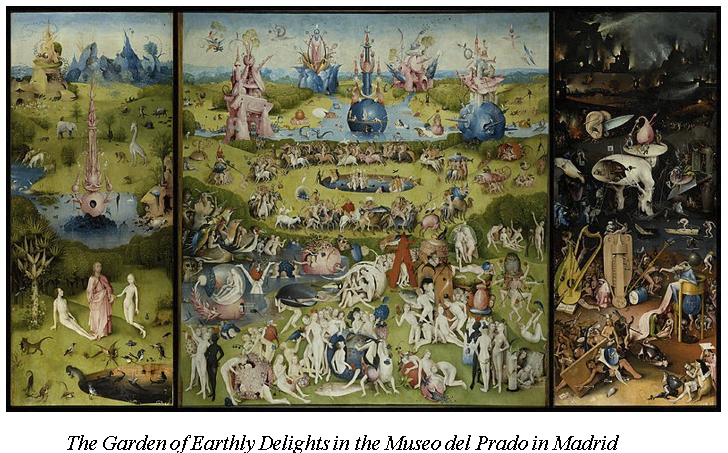

In recent years, art historians have added a further dimension again to the

subject of ambiguity in Bosch’s work. They emphasized his ironic tendencies,

which are fairly obvious, for example, in the The Garden of Earthly Delights,

both in the central panel (delights),[13] and the right panel (hell).[14] By adding

irony to his morality arenas, Bosch offers the option of detachment, both from

the real world and from the painted fantasy world. By doing so he could gain

acceptance among both conservative and progressive viewers. Perhaps it was

just this ambiguity that enabled the survival of a considerable part of this

provocative work through five centuries of religious and political upheaval. A recent study on Bosch’s paintings alleges that they actually conceal a strong

nationalist consciousness, censuring the foreign imperial government of the

Burgundian Netherlands, especially Maximilian Habsburg. By systematically

superimposing images and concepts, the study asserts that Bosch also made his

expiatory self-punishment, for he was accepting well-paid commissions from the

Habsburgs and their deputies, and therefore betraying the memory of Charles the

Bold.

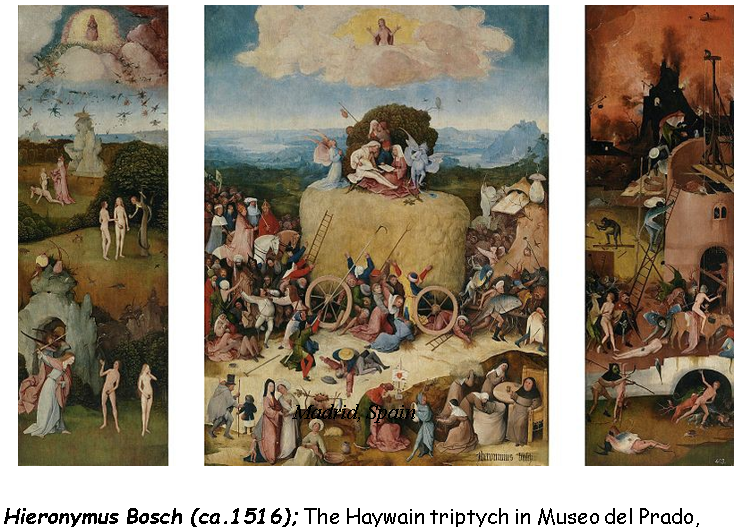

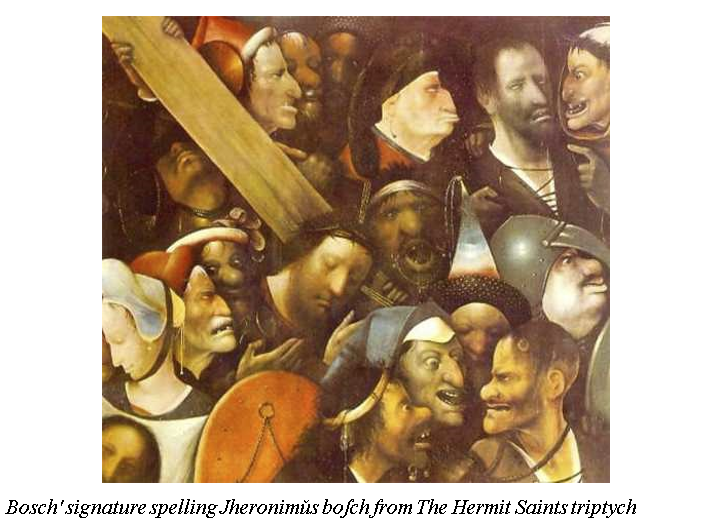

The exact number of Bosch’s surviving works has been a subject of considerable

debate. He signed only seven of his paintings, and there is uncertainty whether

all the paintings once ascribed to him were actually from his hand. It is known

that from the early sixteenth century onwards numerous copies and variations of

his paintings began to circulate. In addition, his style was highly influential, and was widely imitated by his numerous followers.

.

Over the years, scholars have attributed to him fewer and fewer of the works once thought to be his, and today only 25 are definitively attributed to him.

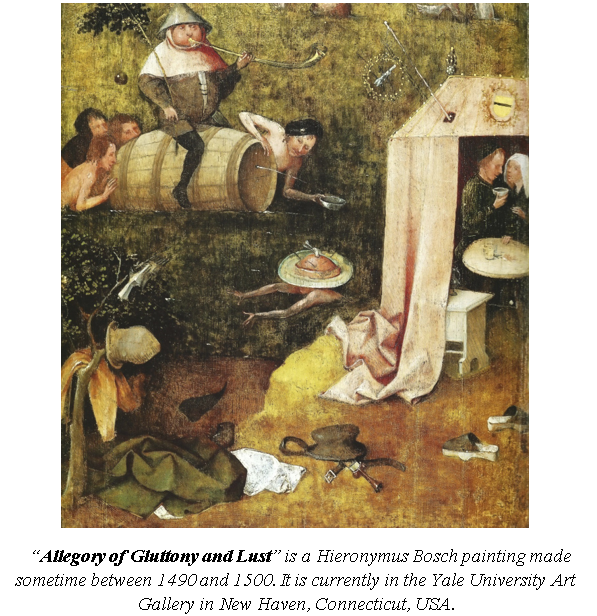

Allegory of Gluttony and Lust is a Hieronymus Bosch painting made sometime between 1490 and 1500. It is currently in the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut.

This panel is the left inside bottom wing of a hinged triptych. The other identified parts are The Ship of Fools, which formed the upper left panel and the Death and the Miser, which was the right panel; The Wayfarer was painted on the right panel rear. The central panel, if existed, is unknown.

The Allegory represented a condemnation of gluttony, in the same way the right

panel condemned avarice. The fragment shows a fat man riding a barrel in a

kind of lake or pool. He is surrounded by other people, who push him or pour a

liquid from the barrel. Below, a man swims with, above his head, a vessel with

meat. The swimmer’s clothes lie on the shore at bottom. On the right, under a

hut, a couple is devoting to lascivious acts, perhaps induced by drunkenness.

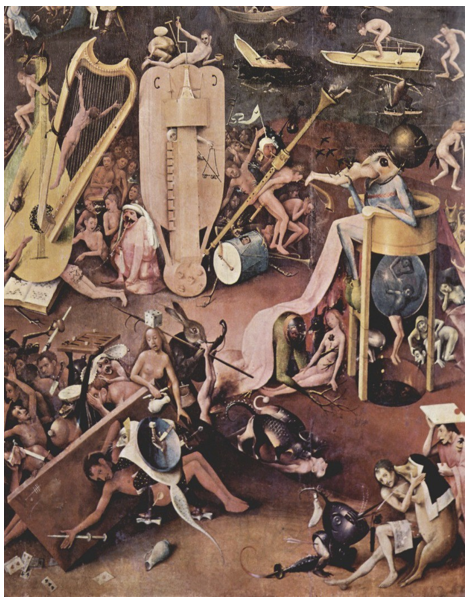

The group of singers form the “yolk” of the egg, which symbolizes “fool” as in

“yokel”. The eel resembles a form of beer (ale). The scene is reminiscent of the

similar Ship of Fools (painting). One of the singers is so intent on his song

(pointing towards the book) that he doesn’t notice that he is being robbed by the

lute player.

Modern attribution of the painting (to an as yet anonymous follower of Bosch)

was based on an analysis of the music in the open book, which shows notes by

Thomas Crecquillon from 1549. The work was bought in 1890 for 400 francs by

the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille from Morhange, a parisian art dealer. It was

featured with the Dutch title “Zangers en Musici in een Ei” in an exhibition in

2008 at the Noordbrabants Museum, ‘sHertogenbosch, the Netherlands.

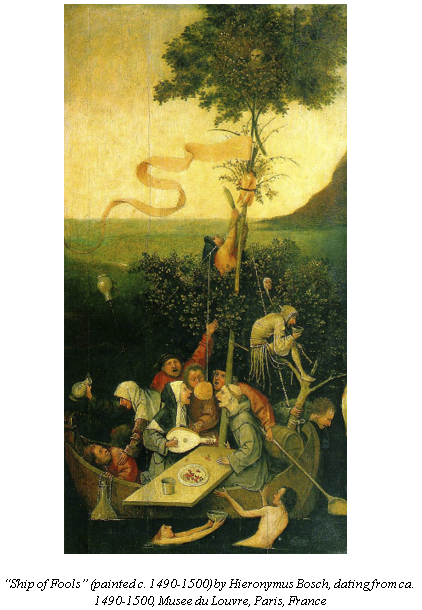

“Ship of Fools” now on display in the Musée du Louvre, Paris. The painting is dense in symbolism and is indebted to, if not actually satirical of Albrecht Dürer’s frontispiece of Sebastian Brant’s book of the same name.

The painting as we see it today is a fragment of a triptych that was cut into

several parts. The Ship of Fools was painted on one of the wings of the

altarpiece, and is about two thirds of its original length. The bottom third of the

panel belongs to Yale University Art Gallery and is exhibited under the title

Allegory of Gluttony. The wing on the other side, which has more or less

retained its full length, is the Death and the Miser, now in the National Gallery

of Art, Washington, D.C. The two panels together would have represented the

two extremes of prodigiality and miserliness, condemning and caricaturing both.

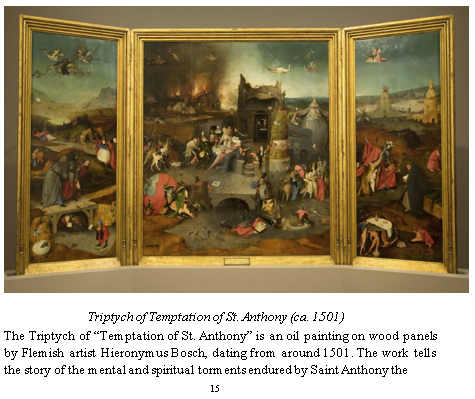

Great (Anthony Abbott), one of the most prominent of the Desert Fathers of Egypt in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries. The Temptation of St Anthony was a popular subject in Medieval and Renaissance art. In common with many of Bosch’s work, the triptych contains much fantastic imagery. The painting hangs in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, in Lisbon, Portugal.

The work tells symbolically the story of the mental and spiritual torments

endured by St. Anthony Abbott throughout his life. The sources for the subjects

were Athanasius of Alexandria’s Life of St. Anthony, which had been

popularized in the Flanders by Pieter van Os, and Jacopo da Varazze’s “Golden

Legend.”

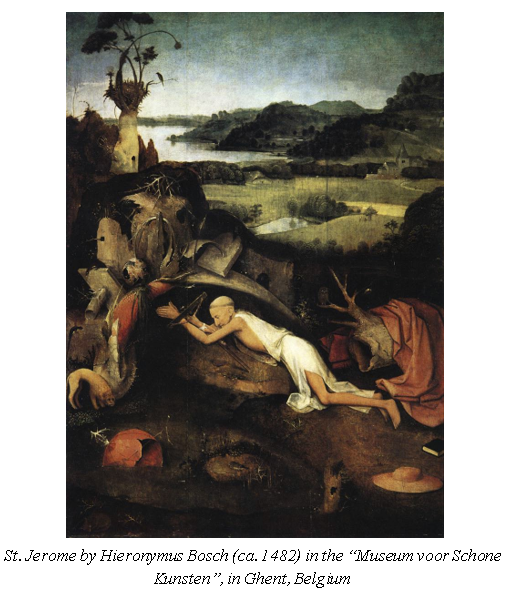

Here, St. Anthony the Abbot is portrayed in meditation, in a sunny landscape

near the trunk of a dry tree. St. Anthony is a recurrent figure in Bosch’s work,

with up to 15 paintings of this subject, all inspired by legends told in the Golden

Legend and in his Life by Athanasius of Alexandria. He is represented in a

setting of solitude and temptation that the saint experienced over twenty years.

Although this picture is significantly different from other works by Bosch of St.

Anthony, such as the triptych painting of the same name, customary features of

the abbot include the his dark brown habit with the Greek letter “tau” and pig by

his side. In contrast to the earlier paintings with St. Anthony, this version of The

Temptation of St. Anthony finds the abbot calmer from his meditative spirit. His

surroundings are peaceful and evoke a sense of calm. The pig lies next to him

like a pet. Once demons, the creatures of temptation are now more like goblins and do not disturb the peaceful feeling of the painting.

St. Jerome was a frequent subject of 15th century European art, depicted in his

studio or during his penitence in the desert. Bosch for this picture adopted the

latter iconography, although his saint is prone instead of kneeling. He is praying

with a crucifix in his arms, also an unusual gesture of communion with Christ. Jerome lies on a rock located under a kind of shell-like cave. He is surrounded

by his traditional symbols (the lion – although in this case it has a smaller size than usual – the galero, the Bible), but Bosch, as common in his works, also

added some bizarre elements, such as the bony pig or the spherical shell

emerging from the pool . This could symbolize the world floating towards

decay.

Am owl and little owl are depicted on a branch: they allude, respectively, to heresy and the struggle against heresy. The Ten Commandments tables can be seen above the cave. The landscape is wide, in green tones.

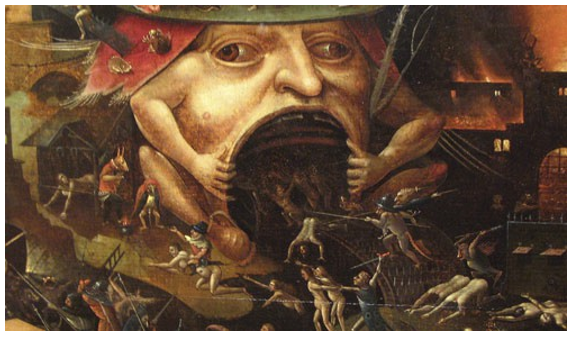

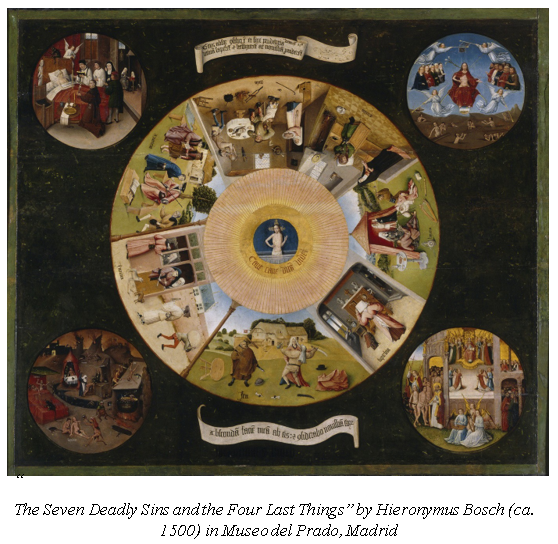

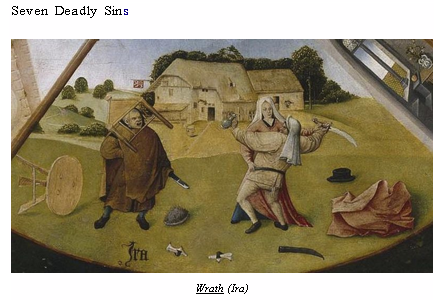

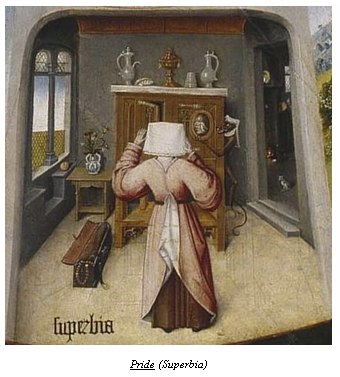

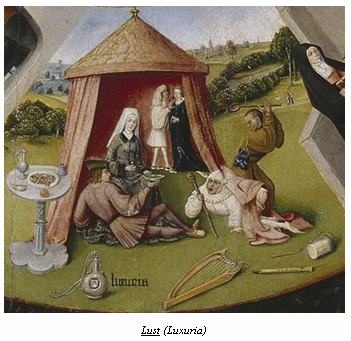

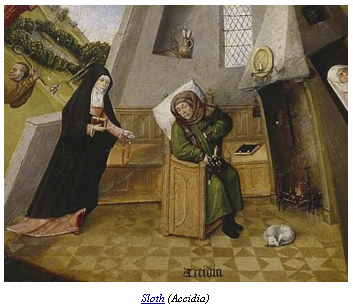

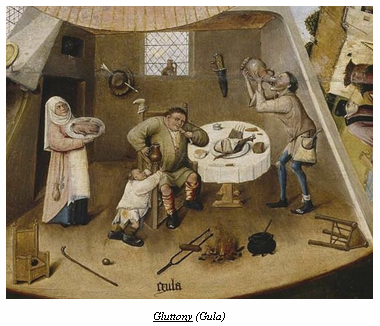

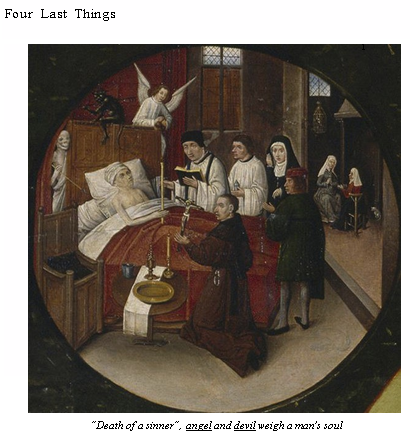

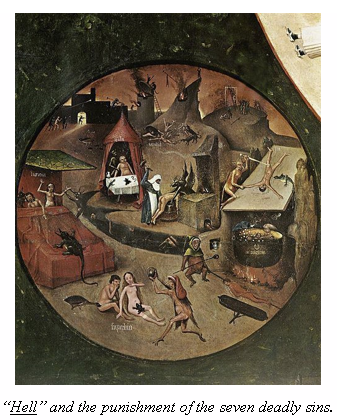

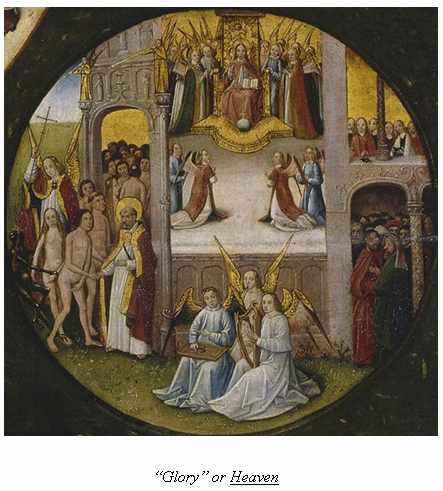

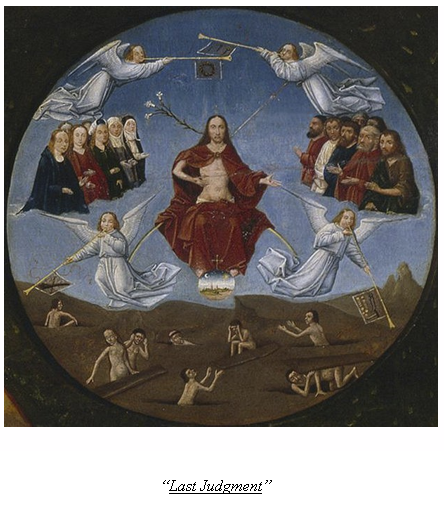

Each scene of the painting depicts a different sin.

In the Pride scene, a demon is shown holding a mirror in front a woman. In

anger, a man is about to kill a woman symbolizing murder as an effect of Wrath.

The small circles also have details. In Death of Sinner, death is shown at the

doorstep along with an angel and a demon while the priest says the sinner’s Last

Rites.

In Glory, the saved are entering Heaven, with Jesus and the Saints, at the gate of Heaven an Angel prevents a demon from ensnaring a woman. Saint Peter is shown as the gatekeeper.

In Judgment, Christ is shown in glory while angels wake up the dead, while in the Hell demons torment sinners according to their sins.

Further examples include Gluttony, where a demon “feeds” a man food of hell.

Another example is the Greed scene, in which misers are boiled in a pot of gold.

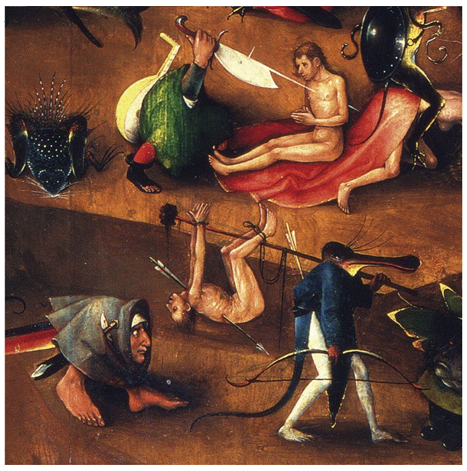

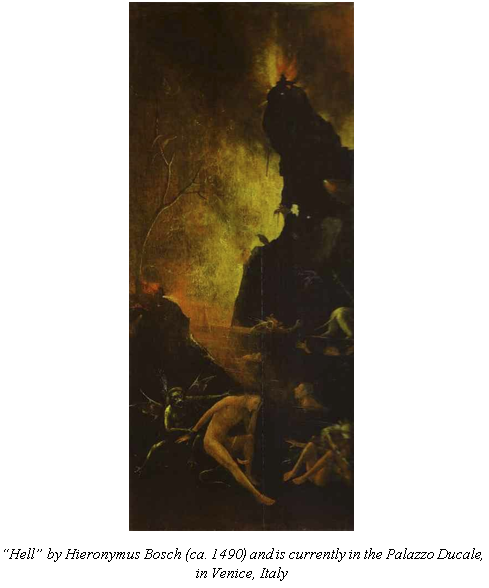

This painting is part of a series of four: the others are Ascent of the Blessed,

Terrestrial Paradise and Fall of the Damned. In this panel, it shows the

punishment of the wicked with diverse kinds of torture laid out by demons.

“Death and the Miser” by Hieronymus Bosch painting. It is currently in the

National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., USA.

Death and the Miser is a Hieronymus Bosch painting. It is currently in the

National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., USA. The painting is the inside of the right panel of a divided triptych. The other existing portions of the triptych are The Ship of Fools and Allegory of Gluttony and Lust, while The Wayfarer was painted on the external right panel.

Death and the Miser belongs to the tradition of the memento mori, works that

remind the viewer of the inevitability of death. The painting shows the influence

of popular 15th-century handbooks on the art of dying (Ars moriendi), intended

to help Christians choose Christ over sinful pleasures. As Death looms, the

miser, unable to resist worldly temptations, reaches for the bag of gold offered

by a demon, even while an angel points to a crucifix from which a slender beam

of light descends.

There are references in the painting to dichotomous modes of life. A crucifix is

set on the only (small) window of the room. A thin ray of light is directed down

to the bottom of the large room, which is darkened. A demon holding an ember

lurks over the dying man, waiting for his hour. Death is dressed in flowing robes

that may be a subtle allusion to a prostitute’s garb. He holds an arrow aimed at

the miser’s groin, which indicates that the dying man suffers from a venereal

disease, which itself may be associated with a love of earthly pleasures.

In the foreground, Bosch possibly depicts the miser as he was previously, in full health, storing gold in his money chest while clutching his rosary. Symbols of worldly power such as a helmet, sword and shield allude to earthly follies — and hint at the station held by this man during his life, though his final struggle is one he must undergo naked, without arms or armor. The depiction of such still-life objects to symbolize earthly vanity, transience or decay would become a genre in itself among 17th-century Flemish artists.

Whether or not the miser, in his last moments, will embrace the salvation offered by Christ or cling to his worldly riches, is left uncertain.